Dodo detectives

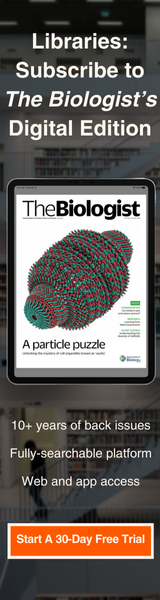

Above: A depiction of a dodo eating invertebrates, by Julian P. Hume.

21 February 2025

Scientists working on a cutting-edge research project to understand the evolution and ecology of the dodo explain how they must first make sense of confusing nomenclature, fanciful Victorian descriptions and non-existent subspecies

Most people think that the dodo was a fat and lazy bird that was doomed when humanity set foot on the island of Mauritius. However, this picture of the bird is at odds with the written accounts of those who saw it in its natural environment. Dutch sailors, for example, reported a fast-moving bird that was at home in the forests of Mauritius and was incredibly difficult to catch once among the trees and rocks.

The dodo and its closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire (also extinct), were large-bodied terrestrial pigeons. The species lived on islands in the Indian Ocean, part of the Mascarene Archipelago, evolving in ecosystems that lacked mammalian predators. This left them defenceless when early settlers arrived and not only began to cut down their forest homes, but brought with them rats and pigs, which began eating birds’ eggs and hatchlings¹.

The descriptions of these two bird species were originally thought so fantastical that, for a time during the 18th and early 19th centuries, they were considered mythological. British naturalist Hugh Strickland in 1848 wrote: “So rapid and so complete was their extinction that the vague descriptions given of them by early navigators were long regarded as fabulous or exaggerated, and these birds, almost contemporaries of our great-grandfathers, became associated in the minds of many persons with the Griffin and the Phœnix of mythological antiquity.”² Only the hard work of Victorian-era scientists eventually demonstrated that the dodo and the solitaire were in fact real animals.

Between 1758 and 1766 three different scientific names were created for the dodo. Image by Julian P. Hume.

Between 1758 and 1766 three different scientific names were created for the dodo. Image by Julian P. Hume.

Our laboratory at the University of Southampton is exploring the evolutionary transition of these bird species from powered flight to terrestrial running. However, before we can investigate comparative biomechanics and explore the major anatomical shifts that occurred during such a transition, we must first clarify how many species of these birds there actually were, the range of variation in the different species and how that is distributed across the various islands in the Mascarene Archipelago.

Unfortunately, there has been great confusion about the number of dodo and solitaire species that lived on the Mascarene Islands. So we must first delve deep into the murky world of dodo and solitaire nomenclature.

What’s in a name?

Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus was the first to name the dodo scientifically. In the 10th edition of Systema Naturæ, published in 1758, Linnaeus created the binomial Struthio cucullatus, putting the dodo in the same genus as the ostrich. However, the name wasn’t based on any specimens or skeletons. He instead based his name on the descriptions that appear in old bibliographic references from the 17th century. The same is true for the second person to name the dodo, French zoologist Mathurin Brisson, who in 1760 called it Raphus raphus.

Linnaeus went on to create another scientific name for the dodo in the 12th edition of Systema Naturæ (published in 1766). There he called it Didus ineptus. Confusingly that meant that between 1758 and 1766 three different scientific names were created for the dodo: Struthio cucullatus, Raphus raphus and Didus ineptus.

For most of the late 18th century and the entire 19th century, biologists used the name Didus ineptus. This was an age when nomenclatural codes, the rules used to create and regulate scientific names, were still being created. The first internationally accepted zoological code of nomenclature went ‘live’ in 1905, and around this time researchers started using a new combination: Raphus cucullatus, the scientific name of the dodo we still use today. The full details of the dodo’s messy naming are even more complicated³.

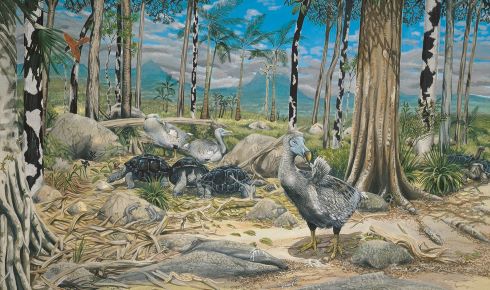

Biologists once thought there may have been two species of dodo on the island of Mauritius. Image by Julian P. Hume.

Biologists once thought there may have been two species of dodo on the island of Mauritius. Image by Julian P. Hume.

The scientific name for the solitaire – Didus solitarius – was established in 1789 by German biologist Johann Gmelin. Like the dodo, the solitaire was named from descriptions of the birds, not specimens – but only one of these works was authored by a person who had actually seen live solitaires in their natural habitat⁴.

The name was altered to Pezophaps solitaria by Strickland in 1848². He established a new genus for the solitaire, Pezophaps, as he thought it was distinct enough from the dodo to warrant it. Under the rules of zoological nomenclature, the grammatical gender of the generic and specific names must match, so the species name solitarius had to change to solitaria.

The species that never were

Biologists once thought there may have been two species of dodo on the island of Mauritius: the hooded dodo (the dodo we know and love today), and the ‘Nazarene dodo’ (Didus nazarenus). This phantom species has an exceptionally baffling history, with some confusing it with the dodo, some with the solitaire, plus other confusion over which islands it was supposedly found on.

It was again Strickland who, in 1848, tried to put things straight, stating that the Nazarene dodo was most likely based on descriptions of a cassowary and that there was no evidence of two dodo species on Mauritius².

Unfortunately, in the 1850s, British zoologist Abraham Bartlett resurrected the name Didus nazarenus for what we now know is the male solitaire. The solitaire had pronounced sexual dimorphism – the greatest of any non-ratite bird – with males noticeably larger than females, and these two ‘morphs’ were for a time thought to be two distinct species. Bartlett called the larger morph Didus nazarenus and the smaller morph Didus solitarius, while Strickland called the larger morph Pezophaps solitaria and the smaller morph Pezophaps minor. It wasn’t until 1866, and the discovery of new specimens of the solitaire, that biologists began to realise it was a sexual dimorphic pigeon⁵ and the names Didus nazarenus and Pezophaps minor died out.

The confusion continues…

As well as the Nazarene, there was also ‘the white dodo’ and the ‘solitaire of Réunion Island’ – based on the idea that there was another species of ground pigeon living on the island of Réunion. It wasn’t until the 1990s and early 2000s that this was conclusively shown not to be the case⁶.

The confusion came from reports of a large bird with white or yellow plumage that once lived on Réunion². When artists made life reconstructions of this animal in the 1850s, it wasn’t of a dodo, but a bird resembling an ibis or a stork. However, by the 1860s artists began to link the mysterious white bird of Réunion with the dodo.

In 1848 Belgian biologist Edmond de Sélys Longchamps named this bird Apterornis solitarius (alongside two more extinct bird species from the Mascarene Islands: A. cœrulescens and A. bonasia). He considered his three new species to all be closely related to the dodo and solitaire. However, A. cœrulescens was later shown to be an extinct species of swamphen, while A. bonasia was shown to be an extinct species of rail.

German naturalist Hermann Schlegel named two more new species of dodo in 1854 – Didus broeckei and D. herbertii. These have both been shown to be the same species as Apterornis bonasia³.

In the late 1930s Japanese ornithologist Masauji Hachisuka hypothesised that Réunion had had its own species of both dodo and solitaire living side by side. He called this ‘Réunion solitaire’ Ornithaptera solitaria and created a new name, Victoriornis imperialis for the ‘white dodo of Réunion’. Unfortunately, Hachisuka’s classification wasn’t based on specimens, but instead on watercolour paintings, and misinterpretations of the accounts of explorers from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Rather than being lazy, Dutch sailors reported the dodo as a fast-moving bird that was incredibly difficult to catch

Rather than being lazy, Dutch sailors reported the dodo as a fast-moving bird that was incredibly difficult to catch

We now know there was no ‘Réunion solitaire’ or ‘white dodo of Réunion’. There was in fact a large-bodied ibis, with white or yellow plumage, which became extinct shortly after humans arrived on Réunion⁶.

So after all that, our latest understanding is that there were only two species of giant ground pigeons living on the Mascarene Islands: the dodo on the island of Mauritius and the solitaire on the island of Rodrigues.

Dodo research today

Since the turn of the millennium, dodo and solitaire research has undergone a renaissance. Their evolutionary relationships among the pigeons are now well understood, their bone histology has been studied, CT scanning has revealed their brain and neurosensory anatomy, and the most complete dodo skeleton known has been described in depth⁷⁸⁹.

Today, research into the dodo is at the cutting edge of science. Now that we can use CT scanning to reconstruct their skeletons digitally, we can investigate what happened to their pelvis and limbs during the flight-to-running transition. This is what the Gostling Evolution and Palaeobiology Lab group at the University of Southampton is currently exploring.

Our collaboration started with a comprehensive look into the nomenclature of the dodo, the solitaire and the entire pigeon family. The resulting paper³ serves as the starting point for our current research programme.

The dodo's closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire, by Julian P. Hume.

The dodo's closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire, by Julian P. Hume.

Our project aims to advance the field of palaeobio-mechanics in two important ways. First, it focuses on the dodo: an iconic species that underwent a major evolutionary transition, but has been the subject of little previous work other than traditional anatomical descriptions of subfossils and historical overviews. Second, it focuses on how the locomotion of these bizarre pigeons adapted as they transitioned from powered flight to terrestrial running.

Locomotion is a key aspect of how animals interact with their environment, so by studying dodo and bird biomechanics we will get unparalleled insight into how biology and behaviour – not just skeletons and body form – changed across a major transition.

We hope that this exciting project piques the interest of other members of the Society. Our project is interdisciplinary, combining the expertise of palaeontologists, anatomists and biomechanists. We are currently applying for funding to continue this exciting research, and are open to further collaborations, ideas and discussions.

1) Parish, J. C. The Dodo and the Solitaire: A Natural History, 345 (Indiana University Press, 2013).

2) Strickland, H. E. & Melville, A. G. The Dodo and its Kindred; Or the History, Affinities, and Osteology of the Dodo, Solitaire, and Other Extinct Birds of the Islands Mauritius, Rodriguez, and Bourbon, 141 (Reeve, Benham and Reeve, 1848).

3) Young, M. T. et al. The systematics and nomenclature of the dodo and the solitaire (Aves: Columbidae), and an overview of columbid family-group nomina. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 201(4), (2024).

4) Leguat, F. Voyage et vantures de François Leguat, & de ses compagnons en deux îles désertes des Indes Orientales, 164 (David Mortier, London, 1708).

5) Newton, A. & Newton, E. On the osteology of the solitaire or didine bird of the island of Rodriguez, Pezophaps solitaria (Gmel.). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 159, 327–362 (1869).

6) Hume, J. P. & Cheke, A. S. The white dodo of Réunion Island: unravelling a scientific and historical myth. Arc. Nat. Hist. 31(1), 57–79 (2004).

7) Shapiro, B. et al. Flight of the dodo. Science 295(5560), 1683 (2002).

8) Gold, M. E. L. et al. The first endocast of the extinct dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and an anatomical comparison amongst close relatives (Aves, Columbiformes). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 177, 950–963 (2016).

9) Claessens, L. P. A. M. et al. The morphology of the Thirioux dodos. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 35(supplement 1), 29–187 (2015).

Mark T Young MRSB CBiol is a research Fellow at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton.

Markus O Heller is a professor of biomechanics at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton.

Neil J Gostling is an associate professor in evolution and palaeo-biology, and leads the Gostling Evolution and Paleobiology Lab.

Julian P Hume is a world expert on the dodo, working at the Natural History Museum, London.