If you go down to the woods today...

Mike Follows explores the bizarre biology and behaviour of ticks – and how to avoid the diseases they carry

12th December 2022

They don’t have eyes to see you, but they are waiting for you, too small to be spotted easily, but eager to feed on your blood. We are talking about ticks of course, tiny parasitic arachnids second only to mosquitoes as vectors of human disease.

According to research by scientists at Kunming Medical University in China, more than 14% of people worldwide, including famous figures such as Justin Bieber[1], have contracted tick-borne Lyme disease. In 2021 there were 1,146 laboratory-confirmed cases in the UK, but there could have been 2,000 more unreported or undiagnosed.

There are about 20 species of tick in the UK, but climate change is expected to change the distribution of ticks across Europe, potentially increasing our tick population[2]. International travel[3] and bird migration[4] could also introduce more species. Understanding more about ticks’ biology, distribution and behaviour can help us identify Lyme disease hotspots and reduce the risk of being bitten and infected.

Ticks are classified into two major families: hard ticks (Ixodidae) and soft ticks (Argasidae). The hard ticks have beak-like mouthparts and a hard shield called a scutellum on their dorsal surface. With so much diversity among the tick families we will focus on the castor bean tick (Ixodes ricinus), sometimes known as a sheep or deer tick, the only UK species known to be a vector of Lyme disease.

The castor bean tick (Ixodes ricinus), the only tick that carries Lyme disease in the UK

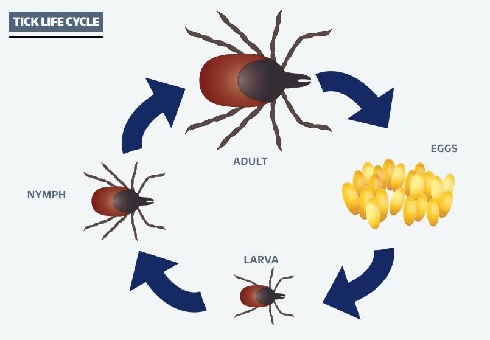

The castor bean tick (Ixodes ricinus), the only tick that carries Lyme disease in the UKThere are four stages to a tick’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph and adult. A female tick will eat just three meals in its life – taking one blood meal at each juvenile stage and one as an adult to help mature up to 2,000 eggs. Many adult males do not bite and so may have only two meals in their entire life. A tick hatches out of its egg as a larva no bigger than the full stop at the end of this sentence. It cannot transmit Lyme disease because it is not born with the infection. Most species of tick, including our deer tick, move slowly and have no eyes. They use Haller’s organs in their front legs to locate potential hosts by detecting odours, humidity, temperature and carbon dioxide, and at this stage tend to target smaller animals such as birds, rodents, reptiles and amphibians.

Once a larva finds and bites a host, it will feed for three days before dropping to the ground to digest its ‘breakfast’ and moult into a nymph. If its first host is infected with the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium responsible for Lyme disease in humans, the bacteria will migrate to the mid-gut of the nymph to hitch a ride to the next host.

Quest for a host

While the larva has six legs, the nymph has eight (in keeping with being an arachnid). Each leg is covered in short, spiny hairs and ends in a tiny claw. These help ticks grasp vegetation and transfer and cling to their hosts. Ticks wait on the tips of vegetation or long grass, reaching out with their front legs in a process called questing. But this is no cute hobbit adventure. The tick wants to feed on anything with a pulse – including you. It needs its potential hosts to brush past.

As they move through the different stages of their life cycle, ticks grow bigger and tend to feed on larger animals. However, even larvae and nymphs will feed on humans given the opportunity. Once attached, they instinctively crawl upward, aiming to attach around the head and neck because the skin there is thinner, and many animals cannot reach them to groom them off. Ticks may also head for areas where they are harder to detect, giving them more time to feed.

Mouthparts vary between tick species, but are generally protected by two palps that move aside during feeding time. This reveals two appendages known as chelicerae, which flank a hypostome. This harpoon-like structure is armed with backward-facing barbs that anchor the tick into the skin. With a sort of swimming motion, the chelicerae cut the host’s skin apart so the hypostome can be inserted[5].

After secreting an anaesthetic saliva to ensure the host remains blissfully unaware of the bite, the tick uses a muscular pump to drink the blood. Tick saliva also includes chemicals to suppress the host’s immune system, prevent blood clotting, break down tissue and help blood to pool under the surface of the skin. When the host’s blood reaches the tick’s mid-gut, any Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria present migrate through the gut wall to the salivary glands, from where they can then enter the host. Infection of a host typically takes one to two days, which is why time is of the essence if you’ve been bitten by a tick[6].

Lurking lyme

To avoid fatal desiccation in the long hiatus between meals, ticks need access to a microclimate with a relative humidity of about 80%[2]. They spend most of their time on the ground, only leaving the protection of vegetation or leaf litter to find a meal.

Larval ticks can be dismissed as a nuisance as they do not carry the bacterium that causes Lyme disease (and rarely bite humans). Nymphs, however, might be more hazardous than adult ticks, partly because nymphs are smaller and more difficult to detect and partly because they are more likely to be infected than adults. This is because an infected nymph can be cleared of its Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria by the immune system of the animal it bites. The nymph will then moult into an uninfected adult. Deer, for example, produce antibodies that help clear the bacteria from the nymph’s system as it feeds.

Nymphs feed in late spring and early summer, accounting for upwards of 80% of infections. May, June and July are the big risk months, partly because more people are outdoors. The larger and more noticeable adult ticks feed in spring and early summer.

The classic symptom of first-stage Lyme disease is the erythema migrans, a bulls-eye rash, although this is not always present. Flu-like symptoms are more common. Without the presence of the rash, first-stage Lyme disease can only be suspected and a precautionary two- or three-week course of antibiotics administered. Without treatment the Lyme bacteria may go on to infect the nervous system, joints and heart, triggering symptoms of second-stage Lyme disease. In extreme cases victims can suffer from Bell’s palsy, a painful condition where muscles on one side of the face become weak or paralysed. The disease can also cause meningitis, with its associated headache and stiff neck.

The third stage occurs months or even years later: late Lyme arthritis, where fluid accumulates in a joint, usually a knee, causing pain. (An outbreak of joint arthritis among young children in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975 is how Lyme disease was discovered.) It is important to keep things in perspective: according to the UK Health Security Agency, only between 2.5% and 5.1% of ticks are infected[7].

The presence of antibodies to the bacterium can be established with an ELISA blood test and Lyme infection can be confirmed with a Western blot test. As antibodies take weeks to develop, this two-tier testing strategy should not be administered too early. Hopefully tests will be developed that directly measure the infection, much like the PCR test for COVID-19, and work on a vaccine is under way.

The life cycle of a tick. Each juvenile and adult feeds once to mature the next stage.

The life cycle of a tick. Each juvenile and adult feeds once to mature the next stage. Avoidance is key

What can we do, short of donning white hazmat suits before we journey outside? Where possible keep to paths and avoid walking through deep vegetation such as ferns. If practical, keep your legs covered to make it harder for ticks to reach your skin. Tuck shirts into trousers and tuck trousers into socks. Ticks have trouble climbing wellington boots, and scientists who go out collecting ticks sometimes use double-sided tape to trap any ticks climbing their trouser legs. Permethrin-impregnated clothing provides good protection against ticks, as well as a variety of other biting insects. Research from 2010 suggests that DEET concentration needs to exceed 33% to be effective[8].

Showering can help wash off ticks that have not latched on, followed by a visual check. Given that ticks are difficult to spot – even hungry adults can be smaller than sesame seeds – feeling for them might be more effective. Favourite places for them are along the waistline, in the armpit, behind the ears, on the neck and on the scalp, particularly along the hairline in children. Pay attention to folds of skin, especially behind the knee and in the groin. You might want to invest in a make-up mirror if you want to check areas that your best friend might not be too eager to investigate.

Most people think cockroaches are almost indestructible, but ticks are at least a match for them. Ticks can survive in near vacuum for up to half an hour and they can go without any water for 18 weeks. They can withstand temperatures as low as -18°C for hours and can survive well below freezing for at least a fortnight. This means that they can survive on your clothes for a long time.

Dry clothes placed in a tumble dryer on high heat for more than six minutes should kill ticks, as will washing at a temperature exceeding 54°C[9]. Remember, ticks can also cling to pets before transferring to you as their preferred host. Their robustness and tenacity means that ticks need to be disposed of carefully (if not sent away for identification). Flush them down the toilet, place them in a container of soapy water or alcohol, or sandwich them in sticky tape before throwing them away.

If you are bitten, the sooner you remove the tick, the less chance there is of disease transmission. Use a tick-remover tool – these should be in any first aid kit for those who hike or do outdoor activities regularly. Squeezing a tick with tweezers or fingers risks forcing the contents of its gut into the host, so grip the tick as close as possible to the skin and pull it straight out, without twisting. Steadily increase the force you apply, which might end up being greater than anticipated.

The mouthparts of the tick can remain embedded in the skin, but these do not carry the infection and will eventually work their way out like a splinter. After you have removed your tick, keep it in a sealed container and send it to Public Health England’s Tick Surveillance Scheme with details of when and where you were bitten. They will identify it for you and add the information to their database.

Australians recommend freezing adult ticks in situ with the sprays used to treat verrucas and warts, and covering larval and nymph-stage ticks with head-lice cream or similar treatments that contain permethrin as an active ingredient. A magnifying glass can be used to check that the legs have stopped moving (and the tick is dead) before brushing them off.

A tick removal tool (left) and a pair of tweezers. The latter are sometimes referred to as 'tick squeezers' because they can force the content of the tick's gut into the host.

A tick removal tool (left) and a pair of tweezers. The latter are sometimes referred to as 'tick squeezers' because they can force the content of the tick's gut into the host. The terror of ticks

If we think we’ve got it bad in the UK, the tick species and the pathogens they carry are even more concerning overseas. While UK species ‘quest’ or wait for a passing host, the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), whose range extends throughout the eastern half of the US, can actually pursue their hosts. When a host is detected, nearby ticks will converge from different directions.

The Australian paralysis tick (Ixodes holocyclus) sometimes does what its name suggests, and its gut contents can cause anaphylaxis, but thankfully it is limited to a 20km band down the eastern coastline of Australia. Both I. holocyclus and A. americanum are responsible for alpha-gal allergy (sometimes called mammalian meat allergy), a condition that causes a severe reaction to red meat in anyone infected[10].

As vectors for various diseases, ticks need to be taken seriously. However, we can minimise the risk of infection by adopting sensible strategies such as avoiding tick habitats during the biting season, wearing suitable clothing or using appropriate repellents. Perhaps the UK also needs to invest more in its surveillance of tick populations and the geographical distribution of tick-borne diseases. Research shows that ticks in Europe are increasing their range to include higher latitudes and altitudes in response to climate change. The future distribution, abundance and species diversity at a particular location will depend on many interrelated factors that make predicting future population dynamics a challenge.

1) Dong, Y. et al. Global seroprevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in human populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis, BMJ Glob. Health 7(6), 1–12 (2022).

2) Gray, J.S. et al. Effects of climate change on ticks and tick-borne diseases in Europe. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 593232 (2009).

3) Gillingham, E.L. et al. The unexpected holiday souvenir: the public health risk to UK travellers from ticks acquired overseas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(21), 7957 (2020).

4) Hasle, G. Transport of ixodid ticks and tick-borne pathogens by migratory birds. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3(48), 1 (2013).

5) Richter, D. et al. How ticks get under your skin: insertion mechanics of the feeding apparatus of Ixodes ricinus ticks. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280(1773) (2013).

6) Schwan, T.G. et al. Vector interactions and molecular adaptations of Lyme disease and relapsing fever spirochetes associated with transmission by ticks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8(2), 115–121 (2002).

7) ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2022/04/13/what-is-lyme-disease-and-why-do-we-need-to-be-tick-aware

8) Goodyer, L.I. et al. Expert review of the evidence base for arthropod bite avoidance. J. Travel Med. 17(3), 182–192, (2010).

9) Nelson, C.A. et al. The heat is on: killing blacklegged ticks in residential washers and dryers to prevent tickborne diseases. Ticks Tick-borne Dis. 7(5), 958–963 (2016).

10) Taylor, B.W.P. et al. Tick killing in situ before removal to prevent allergic and anaphylactic reactions in humans: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac. Allergy 9(2), 1–13 (2019).

12) Cairns, V. et al. Incidence of Lyme disease in the UK: a population-based cohort study, BMJ Open 9(7), e025916 (2019).

Mike Follows FRSB is a science teacher and mountain leader.