Black History Month: Remembering Alan Powell Goffe

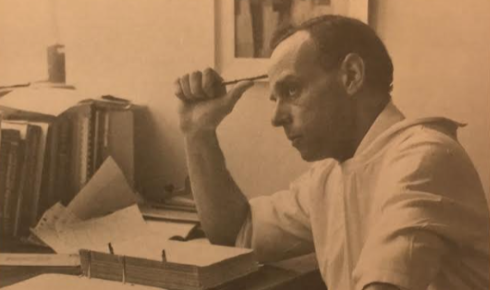

Above: Dr Alan Powell Goffe at his desk at Wellcome.

3rd October 2024

A pioneering Black virologist whose life was cut tragically short

When microbiologist Alan Goffe drowned in the summer of 1966, aged 46, the world lost a brilliant biologist who had been crucial in the development of the first polio and measles vaccines. He was also one of the only Black research scientists to hold a senior role in Britain at the time.

Goffe was born in 1920 to a Jamaican father and British mother, both of whom were doctors. After growing up in Surrey, and attending Epsom College, Goffe went on to study medicine at University College London. He specialised in pathology and began his career at the Central Public Health Laboratories in Colindale, in London, now the site of the UK Health Security Agency. He then gained a diploma in bacteriology in 1947 from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. During his national service, he was stationed in Egypt as a pathologist with the Royal Army Medical Corps.

He then became a senior bacteriologist in the Virus Reference Laboratory at Colindale. He travelled to the USA to learn the latest techniques for cultivating viruses in tissue culture, much of which had been developed by the Nobel Laureate John Franklin Enders. According to the British Medical Journal (BMJ)¹, “nobody realised [the potential of these techniques] better than Goffe,” who immediately began to explore tissue culture as a route to vaccine production in the UK.

The need for vaccines

At this point in the 20th century, outbreaks of polio were killing or paralysing over half a million people every year, and there was an urgent need for a vaccine. Measles was arguably an even bigger problem; the voraciously contagious disease was killing over two million children each year in the 1950s.

In 1955 Goffe joined the virology department at the Wellcome Research Laboratories, expressing his wish to be involved in the eradication of these deadly diseases. “This keen desire to use his special abilities and skills for the alleviation of human suffering was typical of him,” a colleague wrote in the BMJ.

Goffe's work helped make large scale vaccination programmes for diseases like polio and measles safer

Goffe's work helped make large scale vaccination programmes for diseases like polio and measles safer

By the mid-1950s American scientist Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was being distributed across North America. In the early 1960s Albert Sabin then developed an oral polio vaccine that became important for mass vaccination programmes, especially in the former Soviet Union, and for the blockage of transmission.

Goffe helped develop and refine these vaccines, making them safer for use in Britain and for millions of people around the world. He also led the development of an attenuated measles strain known as the ‘Beckenham’ strain (also known as the ‘Goffe’ strain), which formed the basis of many measles vaccines used all around the world. He was among the first scientists to recognise that a monkey virus, SV40, may be contaminating certain vaccines that were being distributed around the world in the 1950s, too. The virus, which can cause tumours in animals, was indeed found to be present in various vaccines estimated to have been distributed to some 30 million people in the United States alone².

During some clinical trials, he publicly tested vaccines on himself and his family to demonstrate his confidence in their safety. He also reviewed vaccines that had already been licenced, for example conducting a study of the efficacy and reactions to US vaccines in UK general practice. He published papers on testing for viruses in sewage, quarantine measures, and the latest laboratory techniques. Goffe’s interest in SV40 led to an interest in the human wart virus, now known as human papillomavirus (HPV). He was among the first to conduct full-scale studies of HPV, building the foundations of research that would go on to discover it to be a cause of cervical cancer.

Two years before the accident that would take his life, he had been honoured by the creation of a new department at Wellcome, set up around his particular talent for developing original, experimental and long-term research in the field of cytology. He was known for being kind to his students and employees, with a friendly and informal manner. He often welcomed foreign scientists to stay at his home and appeared to “know everybody” at international conferences.

Then one day in the summer of 1966, he slipped while sailing off the Isle of Wight and fell into the sea. He was swept away and his body never found, leaving his wife Elizabeth and their four children.

“It can be only speculated how much cytology and science generally have lost by the untimely death of an outstanding scientist at the height of his powers,” wrote a colleague in the BMJ, while The Times eulogised that “his untimely death is therefore the more tragic, for one will never know what his outstanding talents would have contributed to science.”

A lasting legacy

Aged just 46, Goffe had already become Chief Medical Virologist at Wellcome and one of the UK’s most respected virologists. All achieved at a time when racial prejudice was rife and open in Britain, long before specific anti-discrimination legislation came into force. Access to housing, healthcare, educational opportunities, jobs and fair wages were made difficult by racist attitudes and discriminatory policies and practices. “He was almost certainly the only black man to play a prominent role in the world of research science in Britain at the time,” said Gaia Goffe³, who wrote a book abut her late cousin Alan⁴.

At the time of his death, Alan Powell Goffe was also one of the only Black research scientists to hold a senior role in Britain

At the time of his death, Alan Powell Goffe was also one of the only Black research scientists to hold a senior role in Britain

Goffe was a humanitarian as well as a scientist. Not only did he dedicate his career to improving health on a global scale, he was also an early member of organizations such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Freedom From Hunger. He set up a charitable foundation to assist children in Sevenoaks, Kent, after the loss of one of his sons from bone cancer.

Like many Black scientists, his contributions were not widely celebrated and his name is not widely known beyond the virology community. However, recent celebrations of Black History, led by celebrities such as Maggie Aderin-Pocock, have helped raise awareness of Goffe, and how his meticulous scientific work helped save millions of people from the horrors of polio and childhood measles.

Work to completely eradicate these deadly viruses through vaccination is still ongoing, 60 years later. But this epic task is undoubtedly closer to completion thanks to the tireless and trailblazing work of Dr Alan Powell Goffe.

References and further reading

1) A.P Goffe, MP BS DIPL BACT. Obituary Notices, British Medical Journal, 1966 (2), 531.

2) Vilchez R.A. & Butel J.S. Emergent human pathogen simian virus 40 and its role in cancer. Clinical Microbiology Review 17(3), 495-508 (2004).

3) ‘Between two worlds.’ Gaia Goffe, BBCCaribbean.com, 28 July 2008.

4) Gaia Goffe & Judith Goffe. Between Two Worlds: The story of black British scientist Alan Goffe. Hansib Publishing (2008).

Tom Ireland MRSB is editor of The Biologist